The Rise and Fall of the Roman Republic

June 29th, 2024

00:00

00:00

Summary

- Overview of the Roman Republic's transformation

- Founding of Rome in 753 BC by Romulus and Remus

- Expansion fueled by military prowess and key conquests

- Complex political system with checks and balances

- Punic Wars and Julius Caesar's impact

- Assassination of Caesar and rise of Augustus

- Collapse of the Republic and establishment of the Empire

Sources

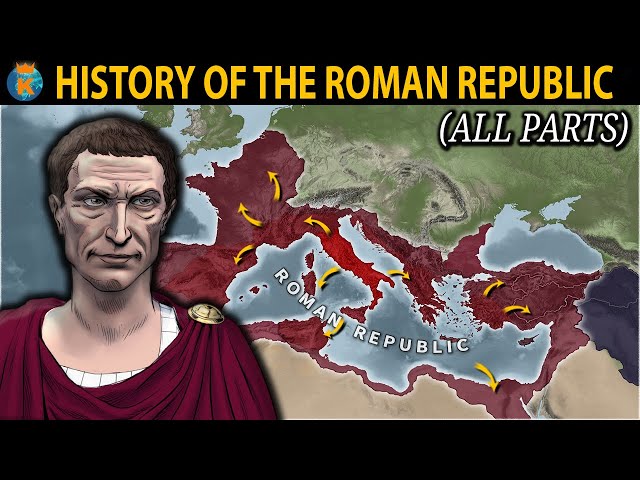

The Roman Republic represents a pivotal era of profound societal and political transformation, leaving an indelible mark on Western civilization. This period, spanning from the founding of Rome in 753 BC to the establishment of the Roman Empire in 27 BC, witnessed significant changes in governance, law, and military might that continue to influence modern society. Legend attributes the founding of Rome to twin brothers Romulus and Remus. According to the myth, Romulus and Remus were abandoned as infants and raised by a she-wolf. Eventually, Romulus killed Remus and became the first ruler of Rome, with the city named after him. While the historical accuracy of this legend is debated, it remains a powerful symbol of Rome's origins. Initially, Rome was a modest agrarian society. Governed by an assembly of citizens, it gradually grew by conquering neighboring city-states and forming a vast network of alliances. This expansion laid the groundwork for what would become one of the most formidable republics in history. The Roman Republic's ascent was driven by its military prowess and adaptability. The Roman army, known for its discipline and tactical brilliance, achieved significant victories across the Mediterranean. Conquering regions like Carthage, Greece, and Macedonia brought immense wealth and resources to Rome, transforming it into a dominant power. A key aspect of the Roman Republic was its complex political system designed to prevent any single individual or group from seizing absolute power. The government was divided into three branches: the Senate, the Assemblies, and the Magistrates. The Senate, composed of elder statesmen, provided advice and guidance. The Assemblies, representing the citizens, made laws, while the Magistrates, elected officials, enforced laws and led the military. This system of checks and balances ensured a delicate balance of power, though it also made the political system susceptible to instability and conflict. The enduring impact of the Roman Republic extends to various aspects of modern governance and law. The Republic's legal system, political institutions, and military strategies have left a lasting legacy. Understanding this period offers valuable insights into the dynamics of power, governance complexities, and the historical influences that continue to shape contemporary societies. The rise of the Roman Republic was marked by a relentless drive for expansion and conquest, which was crucial to its transformation from a small city-state into a dominant power in the Mediterranean. Central to this rise was the exceptional military prowess and adaptability of the Roman army, which played a pivotal role in extending Rome's influence and securing its wealth. Initially, the Roman Republic focused on consolidating power within the Italian Peninsula. By subduing neighboring tribes such as the Samnites and Etruscans, and later Greek colonies in southern Italy, Rome established itself as the preeminent power in the region. This early expansion laid the foundation for further conquests beyond the Italian shores. One of the most significant and defining series of conflicts in Roman history was the Punic Wars, fought against the powerful city-state of Carthage. These wars, spanning from 264 to 146 BC, were a testament to Roman military ingenuity and determination. The first Punic War resulted in Rome's acquisition of Sicily, marking its first overseas territory. The second Punic War, famous for the Carthaginian general Hannibal's daring crossing of the Alps, ultimately saw Rome emerge victorious after the decisive Battle of Zama in 202 BC. The third and final Punic War culminated in the complete destruction of Carthage in 146 BC, bringing vast territories in North Africa under Roman control. The conquests did not stop with Carthage. Rome turned its attention to the Hellenistic world, where the remnants of Alexander the Great's empire presented both an opportunity and a challenge. By 168 BC, Rome had decisively defeated the Macedonian king Perseus at the Battle of Pydna, bringing Macedonia under Roman rule. This victory was followed by the subjugation of Greece, where the Romans dismantled the political autonomy of Greek city-states and integrated them into the growing Roman Republic. The wealth of Greece, with its rich cultural heritage and resources, flowed into Rome, further enriching the Republic. The expansion extended to Asia Minor and the Levant, where Rome confronted and defeated the Seleucid Empire and other regional powers. Each conquest brought not only military glory but also substantial economic benefits. The influx of wealth from conquered territories, including tributes, slaves, and resources, transformed Rome's economy and society. The spoils of war funded public works, infrastructure, and the lavish lifestyles of the Roman elite, while also contributing to the Republic's military capacity. The adaptability of the Roman army was a key factor in these successes. Roman soldiers were trained to be versatile and resilient, capable of fighting in diverse terrains and against various enemies. The Roman legions, known for their discipline and innovative tactics, could quickly adapt to new forms of warfare encountered during their campaigns. This adaptability ensured that Rome could sustain its expansion over centuries, constantly evolving to meet new challenges. In conclusion, the rise of the Roman Republic was inextricably linked to its military conquests and the adaptability of its army. The strategic and tactical brilliance displayed in key conquests such as Carthage, Greece, and Macedonia secured vast wealth and resources for Rome. These military achievements not only enhanced Rome's power but also laid the groundwork for its eventual transition from a republic to an empire. The political system of the Roman Republic was a remarkable framework designed to balance power among various institutions, ensuring that no single individual or group could dominate. This system of checks and balances was crucial in maintaining stability and preventing the rise of tyranny, although it also sowed the seeds for eventual instability. At the heart of the Roman Republic's political structure was the Senate, an assembly of elder statesmen who wielded considerable influence. Composed primarily of patricians, or members of Rome's aristocratic families, the Senate provided advice on policy, foreign affairs, and financial matters. While the Senate did not have formal legislative power, its decisions and recommendations carried significant weight, guiding the actions of other political bodies and magistrates. Complementing the Senate were the Assemblies, which represented the broader citizenry of Rome. The most important of these were the Centuriate Assembly and the Tribal Assembly. The Centuriate Assembly, organized by wealth and military status, was responsible for electing high-ranking magistrates such as consuls and praetors. It also had the authority to declare war and pass laws. The Tribal Assembly, on the other hand, was organized by geographic districts and played a vital role in electing lower-ranking officials and passing legislation related to domestic matters. Magistrates were elected officials who administered various aspects of government and led the military. The most senior magistrates were the consuls, who served as dual executives of the Republic. Elected annually, consuls had the power to command armies, preside over the Senate and Assemblies, and enforce laws. The dual nature of the consulship ensured that no single individual could hold unchecked power, as each consul had the authority to veto the actions of the other. Other important magistrates included praetors, who oversaw judicial matters; quaestors, who managed financial affairs; and aediles, responsible for public works and games. Additionally, censors were elected every five years to conduct the census and oversee public morality. The office of the dictator was an extraordinary magistracy, appointed only in times of dire emergency, with supreme authority but limited to a six-month term. This intricate system of checks and balances was designed to distribute power across multiple institutions, preventing any single faction from gaining absolute control. However, this very complexity also led to conflicts and power struggles. Over time, the balance of power began to shift, particularly as the Senate's influence grew at the expense of the Assemblies. The increasing concentration of power within the Senate, combined with the ambitions of powerful individuals, created tensions within the Republic. Wealthy and influential senators often manipulated the political system to serve their interests, leading to corruption and social unrest. The disparity between the elite and the common citizens widened, exacerbating tensions and fostering a sense of disenfranchisement among the populace. As the Republic expanded, the challenges of governing a vast and diverse territory further strained the political system. Ambitious military leaders, such as Julius Caesar, leveraged their successes on the battlefield to amass personal power and challenge the authority of traditional republican institutions. Caesar's appointment as dictator for life in 44 BC epitomized the erosion of the checks and balances that had once safeguarded the Republic. The assassination of Julius Caesar by senators who feared his growing power was a desperate attempt to restore the Republic's balance. However, it only plunged Rome into further chaos and civil war. The ensuing power struggles ultimately led to the rise of Octavian, later known as Augustus, who established the Roman Empire and centralized power in the hands of a single ruler. In summary, the political system of the Roman Republic was an intricate and balanced framework designed to prevent the concentration of power. The Senate, Assemblies, and Magistrates each played distinct roles in maintaining this balance. However, the system's inherent complexities and the ambitions of powerful individuals gradually destabilized the Republic, paving the way for the emergence of the Roman Empire. The Punic Wars, a series of three protracted and grueling conflicts between Rome and Carthage, were pivotal in shaping the course of Roman history. These wars, fought over control of the Mediterranean, showcased Rome's military tenacity and strategic acumen, ultimately securing its dominance over a vast expanse of territory. The First Punic War, lasting from 264 to 241 BC, marked Rome's initial foray into overseas conquest. The primary battleground was the island of Sicily, where Rome and Carthage vied for control. Despite suffering numerous naval defeats, Rome's persistence paid off with a decisive victory at the Battle of the Aegates Islands, leading to Carthage's withdrawal from Sicily. This conflict marked Rome's emergence as a formidable naval power. The Second Punic War, spanning from 218 to 201 BC, is perhaps the most famous of the three. It featured the legendary Carthaginian general Hannibal, who famously crossed the Alps with his war elephants to invade Italy. Hannibal won several significant battles, including the Battle of Cannae, where his forces inflicted a devastating defeat on the Roman legions. However, Rome's resilience and strategic countermeasures, particularly under the leadership of General Scipio Africanus, eventually turned the tide. Scipio's decisive victory at the Battle of Zama in 202 BC forced Carthage to sue for peace, significantly diminishing its power. The Third Punic War, from 149 to 146 BC, was characterized by Rome's determination to eliminate the Carthaginian threat once and for all. The war culminated in the complete destruction of Carthage after a brutal siege. The city was razed, and its territory was annexed as the Roman province of Africa. This final victory solidified Rome's supremacy in the western Mediterranean and marked the end of Carthage as a major power. The aftermath of the Punic Wars brought immense wealth and resources to Rome, further fueling its expansion and transforming it into an unparalleled power. However, the influx of wealth also exacerbated social inequalities and political tensions within the Republic, setting the stage for internal conflicts. Amid this backdrop of expansion and internal strife, Julius Caesar emerged as a formidable military leader and politician. Born in 100 BC into the Julian clan, Caesar's rise was marked by his extraordinary military campaigns and political acumen. His conquest of Gaul, from 58 to 50 BC, not only expanded Rome's territory but also cemented his reputation as a brilliant commander. The Gallic Wars brought vast riches to Rome and increased Caesar's popularity among the Roman populace and his legions. Caesar's growing power and ambition, however, alarmed many in the Senate. In 49 BC, Caesar crossed the Rubicon River with his army, an act of insurrection that plunged Rome into civil war. His subsequent victory over the forces of Pompey and the Senate led to his appointment as dictator. Caesar's reforms, including the reorganization of the calendar and centralization of the administration, were aimed at stabilizing the Republic, but his accumulation of power increasingly resembled monarchy. The fear of Caesar becoming a tyrant drove a group of senators to conspire against him. Key figures in the conspiracy included Marcus Junius Brutus, Gaius Cassius Longinus, and Decimus Junius Brutus Albinus. Brutus, despite his personal connection to Caesar, was motivated by a strong sense of republican duty and the belief that Caesar's rule threatened the Republic's foundations. Cassius harbored personal animosities and feared losing his influence under Caesar's regime. Decimus, a trusted ally and military commander under Caesar, was swayed by a combination of personal ambition and republican ideals. The conspirators meticulously planned Caesar's assassination, aware that their actions could cost them their lives if discovered. They chose the Ides of March in 44 BC, a date laden with symbolic warnings, to strike. The Senate meeting at the Theatre of Pompey provided a controlled environment where they could execute their plan. On that fateful day, Caesar was stabbed to death by the conspirators, an act they believed would restore liberty to Rome. However, Caesar's assassination plunged Rome into further chaos and civil wars. The power vacuum it created was filled by his allies and successors, most notably Octavian, Caesar's adopted son. The ensuing conflicts ultimately led to the end of the Roman Republic and the rise of the Roman Empire under Augustus. In conclusion, the Punic Wars were instrumental in establishing Rome's dominance, while the rise of Julius Caesar highlighted the Republic's internal vulnerabilities. The motivations and actions of the conspirators against Caesar underscore the complexities of power and the profound impact of individual ambitions on the course of history. The assassination of Julius Caesar on the Ides of March in 44 BC marked a turning point in Roman history, precipitating a cascade of events that led to the fall of the Roman Republic and the rise of the Roman Empire. The immediate aftermath of Caesar’s death was chaotic, plunging Rome into a series of civil wars as various factions vied for power. In the wake of the assassination, Caesar’s supporters and the conspirators quickly clashed. Mark Antony, a loyal ally of Caesar, initially sought to maintain order but soon found himself in conflict with the Senate and the leading conspirators, including Brutus and Cassius. The power struggle intensified when Octavian, Caesar’s adopted son and heir, entered the fray. Octavian, who would later be known as Augustus, was a shrewd and ambitious young man determined to claim his inheritance and avenge Caesar’s death. The ensuing civil wars saw shifting alliances and brutal battles. Initially, Octavian and Mark Antony allied against the forces of Brutus and Cassius, culminating in the decisive Battle of Philippi in 42 BC, where the conspirators were defeated. However, the alliance between Octavian and Antony was fraught with tension and mistrust. Antony’s involvement with Cleopatra, the Queen of Egypt, further complicated matters, leading to a propaganda war that painted Antony as a traitor to Rome. The final confrontation between Octavian and Antony took place at the Battle of Actium in 31 BC. Octavian’s naval forces, commanded by his general Agrippa, decisively defeated Antony and Cleopatra’s fleet. Following their defeat, Antony and Cleopatra fled to Egypt, where they ultimately committed suicide. With his rivals vanquished, Octavian returned to Rome as the unchallenged ruler. In 27 BC, Octavian formally ended the Roman Republic by accepting the title of Augustus, becoming the first Roman Emperor. This event marked the official establishment of the Roman Empire, characterized by centralized power and an imperial system of governance. Augustus implemented a series of reforms that stabilized the state, reorganized the military, and initiated a period of relative peace and prosperity known as the Pax Romana. The transition from Republic to Empire was not merely a change in political structure but a transformation in the nature of Roman governance. The Republic, with its complex system of checks and balances, had been designed to prevent the concentration of power. However, the expansion of Rome’s territories and the resulting social and economic changes had strained this system to its breaking point. The rise of powerful individuals like Julius Caesar exposed the Republic’s vulnerabilities, leading to its eventual collapse. Despite its fall, the legacy of the Roman Republic endures in many facets of modern society. The Republic’s legal system, particularly the concepts of codified law and legal precedent, has had a lasting influence on Western legal traditions. The idea of a republic governed by elected representatives and checks and balances resonates in the political systems of many modern democracies. Moreover, the cultural and intellectual achievements of the Roman Republic, including advancements in engineering, architecture, literature, and philosophy, continue to be celebrated and studied. The Republic’s emphasis on civic duty and public service remains a foundational ideal in contemporary civic life. In conclusion, the assassination of Julius Caesar set into motion a series of events that led to the demise of the Roman Republic and the rise of the Roman Empire under Augustus. The fall of the Republic was a complex process driven by internal conflicts, ambitious individuals, and the challenges of governing an expanding territory. However, the legacy of the Roman Republic, with its contributions to law, governance, and culture, continues to shape and inspire modern societies.