Visakhapatnam's Ancient Marvel

May 24th, 2024

00:00

00:00

Summary

- Explore Simhachalam temple's history

- Architectural ingenuity of ancient India

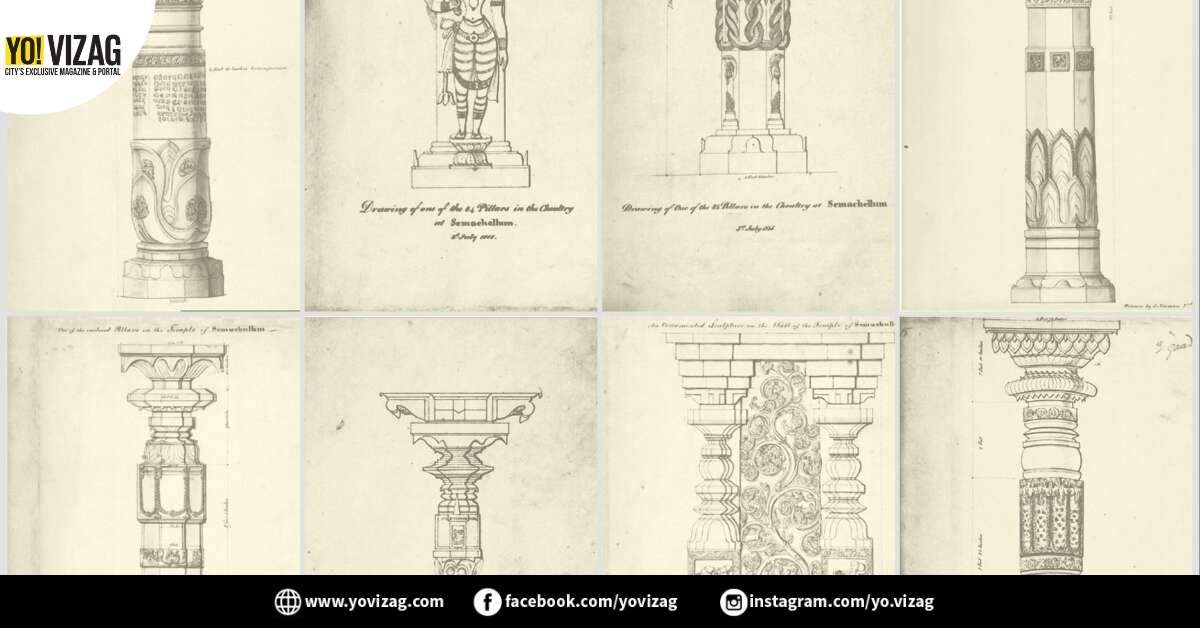

- Colonel Mackenzie's documentation efforts

- Cultural heritage and imperial grandeur

- Multicultural team's role in preservation

Sources

Nestled on a verdant hill in Visakhapatnam lies the Simhachalam temple, a place where history and spirituality intertwine with the natural landscape. This sacred site is not only a nexus of devotion but also a testament to the architectural ingenuity of ancient India. The temple's storied past traces back to the 8th century, under the reign of the Kalinga Empire, when the name 'Simhachalam'—meaning 'the hill of the lion'—first emerged. The etymology is fitting; after all, this is the abode of Varaha Narasimha, a deity revered as the lion-man avatar of Lord Vishnu. The aura of antiquity is palpable as one explores the temple's complex, with carvings etched into pillars, walkways, and structures providing a rich tapestry of the past. These engravings are historical records in stone, chronicling the legacy of rulers, their customs, and the social life that once thrived here. Varaha Narasimha, the temple's presiding deity, represents a fusion of the divine forms Narasimha and Varaha, echoing the syncretism prevalent in the region's religious expressions. The temple's location on the Kailasa hill range serves as a natural boundary to Visakhapatnam. The materials used in its construction, primarily granite and charnockite rock, are sourced from the surrounding area, shaping the temple not just in a figurative sense but in a very literal one too. The dark-hued charnockite lends a distinctive character to the temple's Asthana Mandapa and Kalyana Mandapa, the assembly and marriage halls, respectively. While the Simhachalam temple has been an anchor of faith for centuries, its architectural marvels remained largely unknown to the outside world until the early 19th century. It was then that Colonel Colin Mackenzie, a Scottish army officer and the first Surveyor General of India, stumbled upon this jewel during his surveys. Mackenzie's extensive mappings and recordings of local histories, rulers, and topographies, including the Simhachalam temple, have provided an invaluable trove of information for historians and anthropologists. His sketches of the temple from 1815 offer a glimpse into a world where religion and empire intersected. Mackenzie's accomplishments were a product of his collaboration with Indian assistants, who brought their expertise and local knowledge to the fore. This multicultural team of researchers, draftsmen, copyists, and surveyors meticulously captured the details of the Simhachalam temple, from its pillars to its inscriptions, ensuring that its legacy would endure. The temple's architectural features, such as the prakaras and the towering gopuram, are characteristic of South Indian temple design but also stand as symbols of imperial grandeur. Inscriptions within the temple premises reveal the identities of its patrons, including one that commemorates the 16th-century conquests of Krishna Raya, a Rajah of Vizayanagar, whose contributions to the temple are etched into its very stones. Through the discovery and documentation efforts led by individuals like Mackenzie and his team, the Simhachalam temple has been firmly etched into the broader narrative of India's cultural heritage. The sketches of its columns and the inscriptions that adorn its walls are not merely artistic accomplishments; they are historical dialogues carved into rock, inviting us to listen to the stories they have to tell. For those who wish to delve deeper into this architectural narrative, high-resolution images of these sketches are available in the vast archives of the British Library. As the temple continues to stand resolutely against the landscape, it serves as a bridge to the past, offering insights into the Kalinga Empire, the devotion to Varaha Narasimha, and the very etymology of 'Simhachalam'. It is a testament to the enduring nature of historical and architectural significance, bridging centuries and connecting civilizations. Continuing the narrative, the legacy of Colin Mackenzie extends far beyond the stone carvings and inscriptions of the Simhachalam temple. This Scottish army officer, who rose to become the first Surveyor General of India, led a life dedicated to the pursuit of knowledge and the documentation of a land that was, at the time, largely a mystery to his contemporaries in the Western world. His tenure in India spanned four decades, a period marked by an insatiable curiosity about the subcontinent's diverse cultures, histories, and geographies. Mackenzie's work was no ordinary feat of cartography or surveying; it was an ambitious project that would eventually map over forty thousand square miles of South Indian terrain. His contributions were not confined to the creation of maps alone. He collected a vast array of data that included manuscripts, sketches, paintings, coins, and artefacts. This compilation of historical data was unparalleled in its scope and scale, and it was instrumental in changing Western perceptions of India. Through the Mackenzie Collection, the Western world gained a new appreciation for the architectural, cultural, and religious marvels of the Indian subcontinent. The sketches produced by Mackenzie and his team in 1815 of the Simhachalam temple's pillars are a testament to their meticulous approach to preservation and understanding. These sketches were part of a broader effort to document and analyze the monumental heritage of places like Konarak, Amaravathi, Mahabalipuram, and, of course, Simhachalam. Mackenzie's approach to his work was characterized by his engagement with the Madras School of Orientalism, which sought to comprehend the monuments and relics of India through dedicated and methodical research. His discoveries, which included significant historical insights into Jainism and the first Western description of the magnificent statue of Gommateshwara, were pioneering. He also unearthed the long-forgotten relics of Amaravati, revealing a chapter of Buddhist art and architecture that had been buried under the sands of time. The intellectual foundations of Mackenzie's legacy can be attributed to his effective management and guidance of a team of Indian assistants, who shared his passion for discovery and scholarship. The collaboration with local researchers like Cavelly Venkata Boraiah and Cavelly Lakshmaiah, among others, was crucial to the depth and accuracy of his findings. Mackenzie's ability to direct and utilize the knowledge of local experts was pivotal in the success of his monumental task. This scholarly endeavor resulted in Mackenzie amassing the largest collection of Indian artefacts owned by any European of his time—an enduring monument to his commitment to documenting India's past. His death in India in 1821 marked the conclusion of a life devoted to exploration and understanding, leaving behind a collection that continues to be a cornerstone for researchers and historians. Most of Mackenzie's collection now resides in the British Museum and the British Library, with some artefacts, like the Amaravati Marbles, housed in the Amaravati Gallery of the Egmore Museum in Chennai. These artefacts provide a tangible link to a history that spans two millennia and offer a window into the world's oldest Buddhist art collection. The team Mackenzie assembled at Simhachalam, consisting of draftsmen, copyists, and surveyors, played a vital role in bringing the temple's architectural narrative to light. These individuals, many of whom were educated at the Madras Orphans’ Asylum and apprenticed with the Madras Survey Department, contributed their skills to the preservation of India’s cultural legacy. It is through their efforts and Mackenzie's visionary leadership that the sketches and descriptions of the Simhachalam temple pillars were created, contributing significantly to the world's understanding of India's rich cultural and religious history. The architectural grandeur of the Simhachalam temple is a harmonious blend of form and function, spirituality and stonework. Each element of the temple's design speaks to the artisanal skill and religious devotion of its creators. One cannot help but be in awe of the prakaras, the compound walls that demarcate the sacred spaces of the temple. These walls are not just protective barriers but are integral to the temple's spiritual geography, guiding pilgrims as they move closer to the sanctum sanctorum. Rising above the prakaras is the temple's gopuram, a towering gateway that is as much an architectural marvel as it is a spiritual beacon. This pyramidal structure, adorned with intricate sculptures and carvings, marks the threshold between the mundane and the divine. The gopuram's height and prominence are not accidental; they are designed to draw the eye and the spirit upwards, inviting both devotees and visitors to look beyond the earthly realm. The temple's ancient inscriptions are a testament to the devotion of its patrons and serve as historical documents that offer insight into its storied past. These inscriptions, carefully etched into the hard surfaces of granite and charnockite, have withstood the ravages of time, weather, and human conflict. They recount tales of conquests, donations, and the temple's significance in the lives of those who sought the blessings of Varaha Narasimha. Granite and charnockite, the materials chosen for the temple's construction, are renowned for their durability and strength. The choice of these rocks reflects not only an aesthetic preference but also a deep understanding of their lasting qualities. The granite gives the temple its foundational sturdiness, while the fine-grained charnockite provides the perfect canvas for the temple's intricate carvings found in the assembly and marriage halls. The craftsmanship seen in these structures is a silent ode to the nameless artisans who shaped and sculpted each block with a precision and reverence that transcends time. As the temple stands today, it is not merely an edifice of worship but also a living museum that showcases the pinnacle of temple architecture and the artistry of a bygone era. The Simhachalam temple, through its design and construction, encapsulates the essence of devotion, where every stone and every etching contributes to its sacred atmosphere. The durability of its materials and the timeless nature of its construction techniques ensure that the temple remains a lasting symbol of cultural and religious continuity. The temple's architecture is a tangible expression of the profound spirituality that has imbued this place with an enduring sense of the sacred. The preservation of Simhachalam temple's historical and architectural legacy was not the work of a single individual but the result of a profound collaboration across cultures. At the heart of this exchange of knowledge and skill was Colin Mackenzie, who, in his capacity as a surveyor and historian, recognized the invaluable contributions that could be made by those who were intimately familiar with the local context. It was through this recognition that Mackenzie's multicultural team came into being, a group of Indian scholars, draftsmen, copyists, and surveyors whose collective efforts would document and safeguard the temple's history for posterity. Key figures in this endeavor were Mackenzie's Indian assistants, notably Cavelly Venkata Boraiah and his brother, Cavelly Lakshmaiah. These researchers possessed a deep understanding of local customs, languages, and traditions, which allowed them to access and interpret information that would have otherwise remained elusive. Their scholarship and ability to gain the trust of the local populace were instrumental in providing Mackenzie with the nuanced insights needed to accurately record the region's history and cultural heritage. The team's draftsmen were tasked with creating detailed sketches that captured the aesthetic and structural intricacies of the Simhachalam temple. These sketches, which included depictions of the temple's imposing pillars and expansive gopuram, were not mere artistic renditions; they were precise records that reflected the temple's architectural significance. The copyists meticulously reproduced these drawings, ensuring that the information was accurately preserved for future analysis and study. Surveyors, many of whom had been trained at institutions such as the Madras Orphans’ Asylum, brought their mathematical precision and technical skills to the project. Their measurements and mappings provided a comprehensive understanding of the temple's geographical and spatial dimensions, contributing to the broader cartographic efforts led by Mackenzie. This team, diverse in its composition and unified in its purpose, worked in concert to create a detailed archive of the temple's architectural and cultural wealth. The collaborative spirit that underpinned their efforts is a testament to the power of cross-cultural engagement and respect for indigenous knowledge systems. The legacy of this collaboration is not just in the physical preservation of the Simhachalam temple's heritage but also in the demonstration of how different cultures can work together to honor and maintain a shared human history. The diligent work of Mackenzie's team ensured that the Simhachalam temple, with its ancient inscriptions, architectural grandeur, and religious significance, would not fade into obscurity. Instead, it remains a source of inspiration and reverence, a place where history is alive and accessible, thanks to the enduring partnership between a visionary Scottish officer and his devoted Indian colleagues. Through their collective efforts, the temple's narrative continues to be told, teaching and touching new generations who can now appreciate the rich tapestry of the past that it represents.